Maturity in Project Management Series[1]

By Russell Archibald, Darci Prado & Warlei Oliveira

This is the fifth of a series of articles on PPPMM.

Maturity, Success and Competitiveness

One issue that has always attracted the attention of professionals involved in project, program, and portfolio management (PPPM) is to be able to quantitatively demonstrate the value of this practice and to see it recognized by organizations. We believe that the Brazilian Experience with PPPM Maturity has brought an important contribution to this issue. Brazil is the seventh largest world economy (according to The World Bank) and has a dynamic community of project and program management, highlighted by the 14 active chapters of the PMI and the national IPMA-Brazil Association. The Brazilian Experience with PPPM Maturity is distinguished by longevity (since 2005), the range of participants (the 2012 survey had 434 participating organizations), by frank acceptance by the PPPM community, by the huge amount of results given, and by the consistency of those results.

1 – The Brazilian PPPM Maturity Experience

In the Brazilian Experience we have several elements which have improved the understanding of the value of PPPM for organizations, namely:

- A maturity model (Prado-PMMM) launched in 2002 that has been intensively used. This model was described in some detail in our article of March 2014 of the PM World Journal.

- A proven model of categorization of projects (Archibald – Project Category Model). This model was presented in our article of April 2014 of the PM World Journal.

- A website launched in 2005 containing:

- The questionnaire for the evaluation of PPPM maturity within the responding organization. The user receives the result immediately after completing the questionnaire.

- A second questionnaire to obtain the basic characteristics of the organization being evaluated and its project performance indicators.

- The results of several previous studies since 2005.

- Extensive benchmarking information is available online to enable anyone to compare the PM maturity of their organizational departments with similar departments of other organizations, while maintaining complete confidentiality of individual responding organizations.

- Many other relevant documents.

- Everything is accessible without cost.

- A survey of maturity launched in 2005, with the participation of over a hundred volunteers who assisted in creating the site, analyzing the database, charting, document composition, etc.

- The survey results have remained consistent over the years. Importantly, the research has shown that there is a strong relationship between maturity and success (as further discussed below).

- A book (in Portuguese) that teaches you how to work with the subject, including how to assemble a Growth Plan.

- Participation in various conferences to disseminate results.

- Publication of the results of the research by several authors using various means of communication.

- Adoption of the model within various consulting organizations and by various educational institutions.

As a result:

- A large number of organizations have undertaken the assessment of their PPPM maturity and valid, practical growth and improvement plans were created and implemented;

- A large number of students have used the model in their MBA and MSc theses. We even have PhD students who used the model in their theses. Some of these works are in the Virtual Library page on the site www.maturityresearch.com.

All this has created credibility for the Brazilian PPPMM Experience.

2 – The Questionnaires

In the survey the participant responds to two separate and independent questionnaires:

- Questionnaire to assess the PPPM maturity;

- Questionnaire[2] to provide the department performance indicators (success, delays, overflow cost, adherence to scope, etc.) as well as department data, such as lifetime of the PMO, the visibility of the subject into the organization, etc.

In the evaluation of research results many cross correlations can be made between the responses of the two questionnaires. The matrices show cross figures for minimum, average and maximum maturity and indicator data for:

- 4 organization types: private companies, directly and indirectly administered government organizations, and NGOs.

- 24 business areas.

- 10 project categories.

- The size of organization (billing and number of employees).

3 – 2012 Research Global Results

By way of introduction to the topic, we show below a summary of key indicators obtained in the 2012 survey, which included 434 organizations and 8,680 projects:

Average Maturity:

- Maturity: 2.60 (scale 1 to 5)

Average Performance Indicator Results:

- Success Index:

- Total Success: 49.7%

- Partial Success: 35.2%

- Failure: 15.1%

- Delay: 28%

- Cost Overrun: 15%

4 – Performance Indicator Results

To fully understand this section it would be better if the reader could read the third article (March 2014) of this series that describes the Prado Model in some detail. To facilitate the understanding, we show below the definitions of the five levels of Prado-PMMM:

- Level 1 (Ad Hoc): There is no practice of formalized project management (PM).

- Level 2 (Known): PM is known by leading participants in the organization. The PM initiatives are isolated and not standardized.

- Level 3 (Standardized): Established standardization of PM processes, tools, organizational structure and strategic alignment of projects are being used. Related skills were developed. Everyone involved follows the PM standards.

- Level 4 (Managed): Identification and removal of the causes of PM anomalies occurs.

- Level 5 (Optimized): Schedule deadlines, cost and quality targets are optimized. The PM processes, tools and organizational structure have also been optimized.

According to the 2012 PM Maturity Research the performance indicators for completed portfolio of projects are:

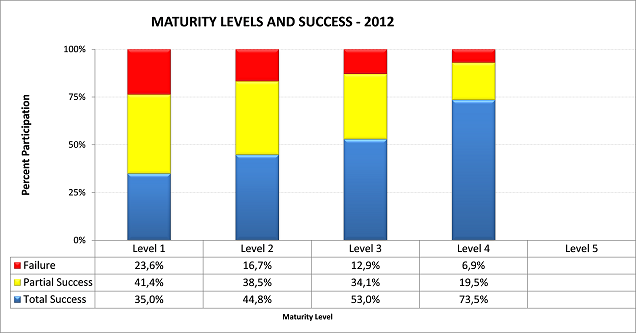

a)Success

The relationships between success and maturity levels are shown in the following graph:

Figure 1: Project Success versus Maturity Levels.

From Figure 1 we can conclude that:

- There is a direct positive relationship between Total Success and Maturity;

- There is an inverted relationship between failure and Maturity.

The site presents various definitions of success, which depends on the category of projects executed by the department; that is, the concept of success for a construction department is different from the concept of a successful IT department. As an illustration, we present below the general definition of success shown on the site.

Total success: A successful project is one that has reached the goal. This usually means it was completed and produced the expected results and benefits and key stakeholders were fully satisfied. In addition, but not mandatory, it is expected that the project has been terminated within the requirements for time, cost, scope and quality (small differences can be accepted).

Partial or challenged success: The project was completed but did not produce the results and benefits expected. There is significant dissatisfaction among key stakeholders. Also, probably some of the requirements for time, cost, scope and quality were significantly exceeded.

Failure: Because there is a huge dissatisfaction among main stakeholders, or the project was not completed, or did not met the expectations of key stakeholders, or some of the requirements for time, cost, scope and quality were exceeded in an absolutely unacceptable way.

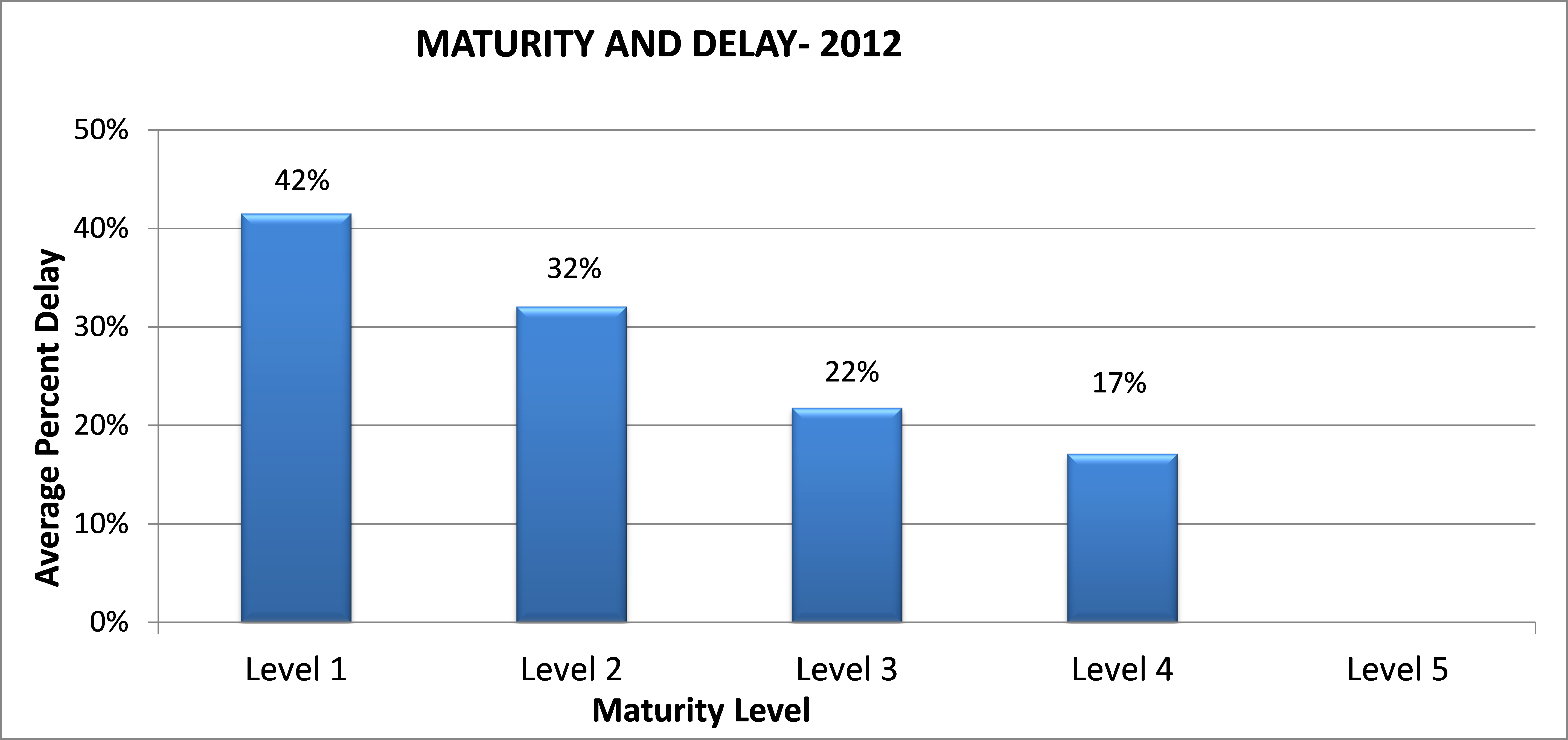

b)Delay

The relationships between project delay and PM maturity levels are shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Project Delay versus Maturity Levels.

From Figure 2 we can conclude that there is an inverse relationship between delay and maturity. The higher the maturity, the lesser the delay.

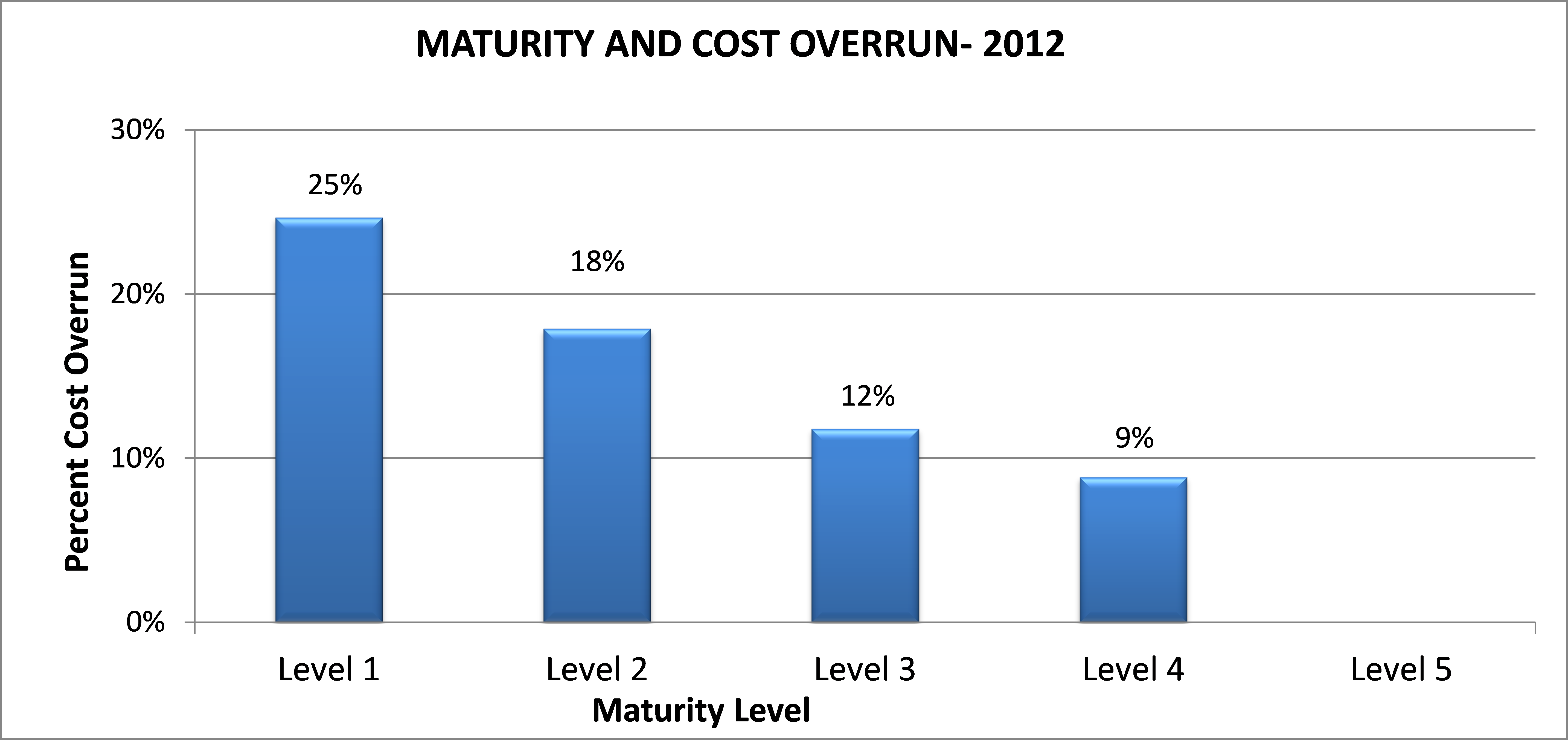

c)Cost Overrun

The relationship between overrun costs and maturity levels are shown in Figure 3:

Figure 3: Project Cost Overrun versus Maturity Levels.

From Figure 3 we can conclude that there is an inverse relationship between Cost Overrun and Maturity. The higher the maturity, the lower overrun costs.

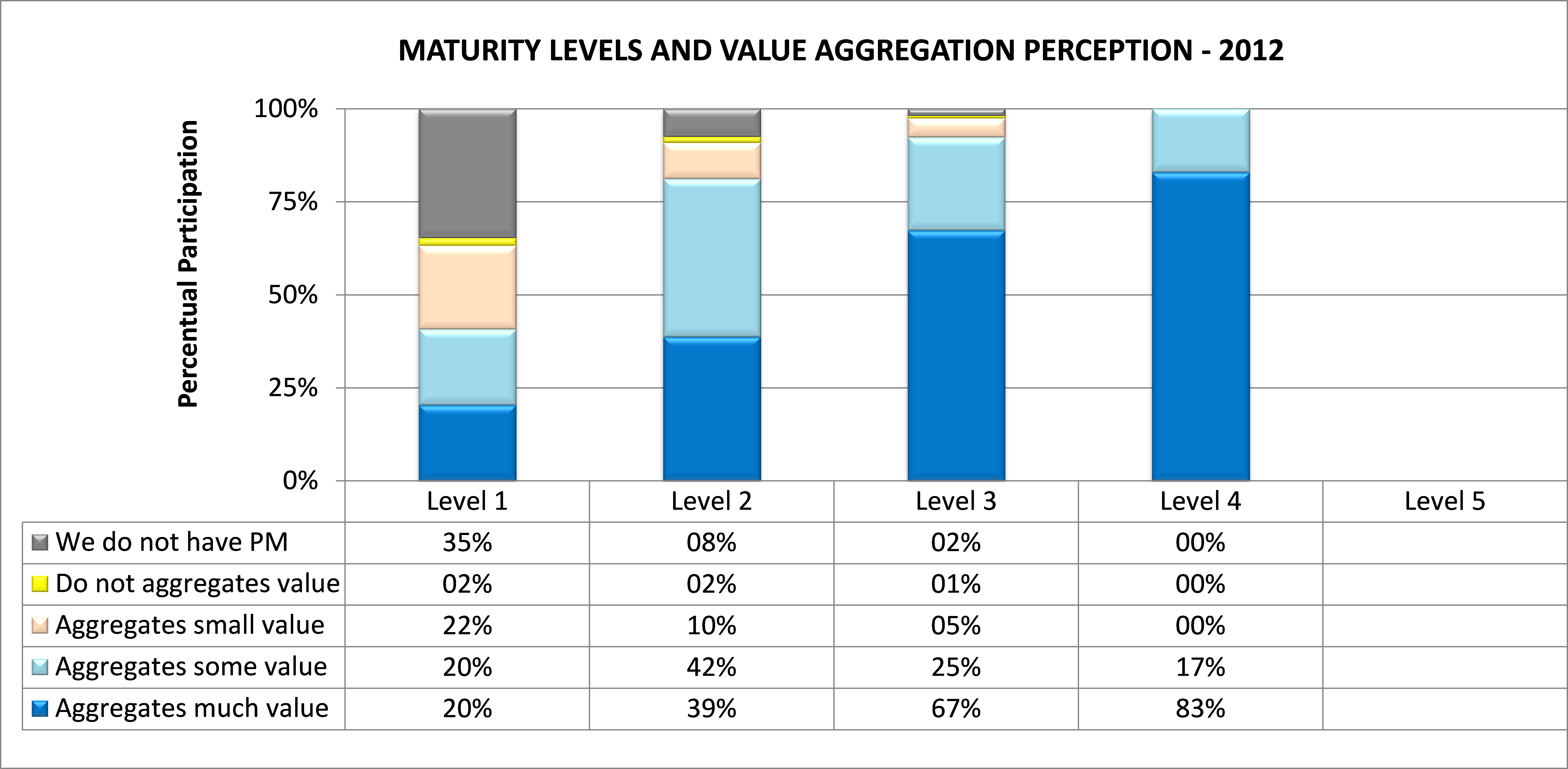

5 – Value Aggregation Results

The question on the perception by key stakeholders of value aggregation by project management is:

19. Regarding the practice of project management (PM) in your department, what is the perception by key stakeholders on the importance (or value creation) that project management brings to the success of projects and / or for the business of the department?

a) PM adds a lot of value

b) PM adds some value

c) PM adds little value

d) PM does not add value

e) We have no PM

The intersection between key stakeholders´ perception of value aggregation by PM and maturity levels are shown in the following graph:

Figure 4: Value Aggregation by PM: Perception versus Maturity Levels.

From Figure 4 we can conclude that there is a direct positive relationship between Perceived Value Aggregation and Project Management Maturity Levels. The higher the maturity, the greater the perception of added value by key stakeholders!

6- Some Additional Important Conclusions

In addition to the conclusions related to each of the four figures presented above, we can draw the following three more general conclusions from these research results:

a)First General Conclusion:

The Figures 1, 2 and 3 allow us to conclude that organizations of higher performance are precisely those of higher mature value according to Prado-PMMM.

That is, the Prado-PMMM is a good tool to measure the performance of projects: the greater the maturity, the higher the performance. Since the Prado-PMMM is based on, in its view, the best practices of project management, we also conclude that the use of good practices really produces better performance.

b)Second General Conclusion:

Figure 4 shows that organizations that have the greatest perception of value aggregation are precisely those that get higher maturity scores, according to Prado-PMMM.

That is, the Prado-PMMM is a good tool to measure stakeholder satisfaction with the use of formal project management practices.

c)Final General Conclusion:

The junction of the two conclusions above leads us to the conclusion that the greater the use of best practices for project management produces higher performance (project success, etc.) and greater recognition by key stakeholders of the importance of the discipline of project management.

That is, the value of using the best practices of project management may be seen in better results and greater recognition by key stakeholders.

This conclusion reveals the great importance of continual improvement in PM practices, especially for organizations that are initiating the use of these practices and are at levels 1 or 2. For them, the daily performance indicators show weak values ??and there is no recognition of the value of project management by senior management. So for such organizations, this study presents a message of optimism: the evolution of maturity will change this scenario. This development does not happen overnight and requires discipline and dedication, but the results are significantly rewarding.

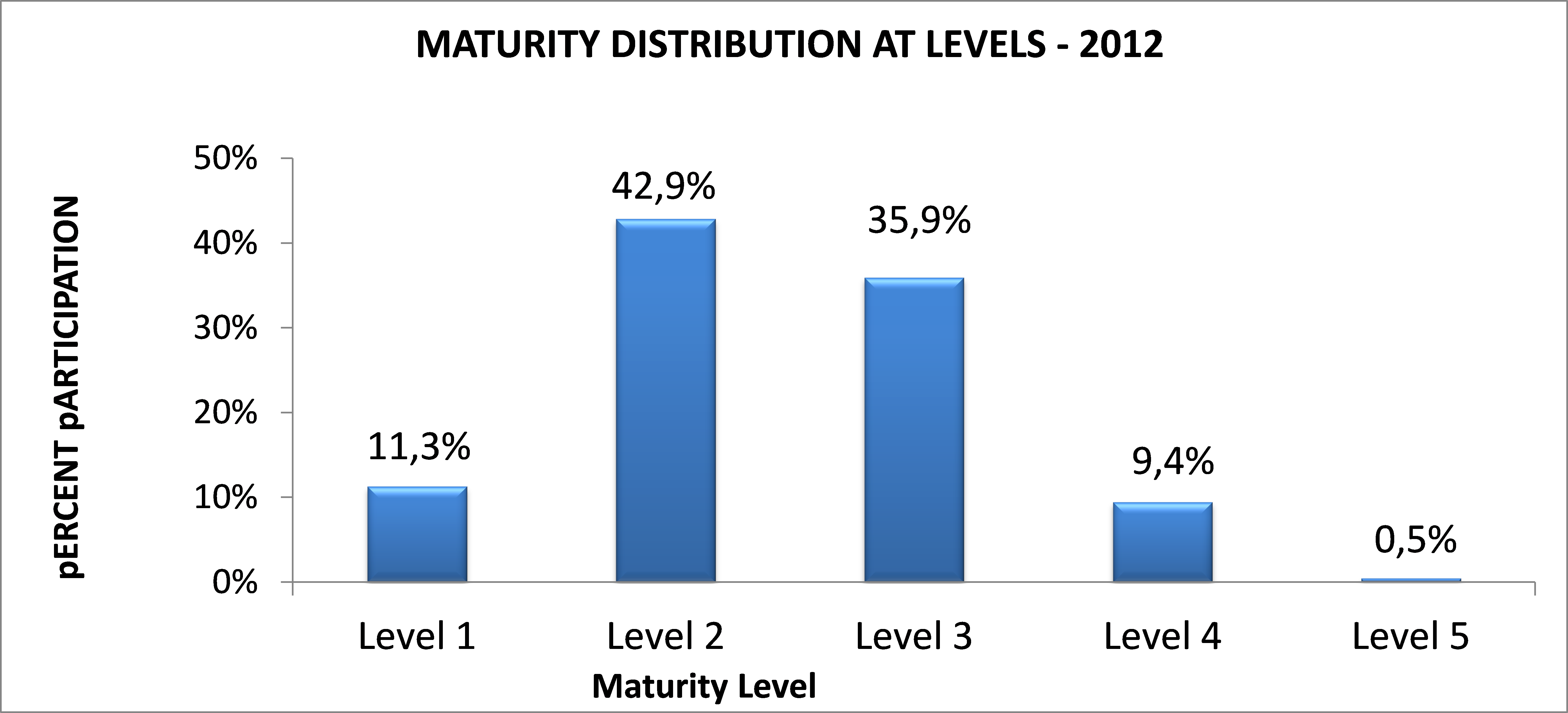

7 – Competitiveness Implications

According to Figure 1, our research substantiates the conclusion that no matter the category of projects executed in your department, if the current maturity is above level 4 the level of success will likely be above 80%. The percentage distribution of PM maturity values for all the participating organizations is shown in Figure 5. In this figure we see:

- Only about 10% of organizations are at the excellence levels (4 and 5);

- About 36% of organizations are in a good level (level 3);

- About 54% of organizations are at weak levels (1 and 2);

Figure 5: Distribution of Participating Organizations in the Five Levels of PM Maturity.

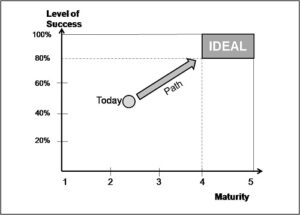

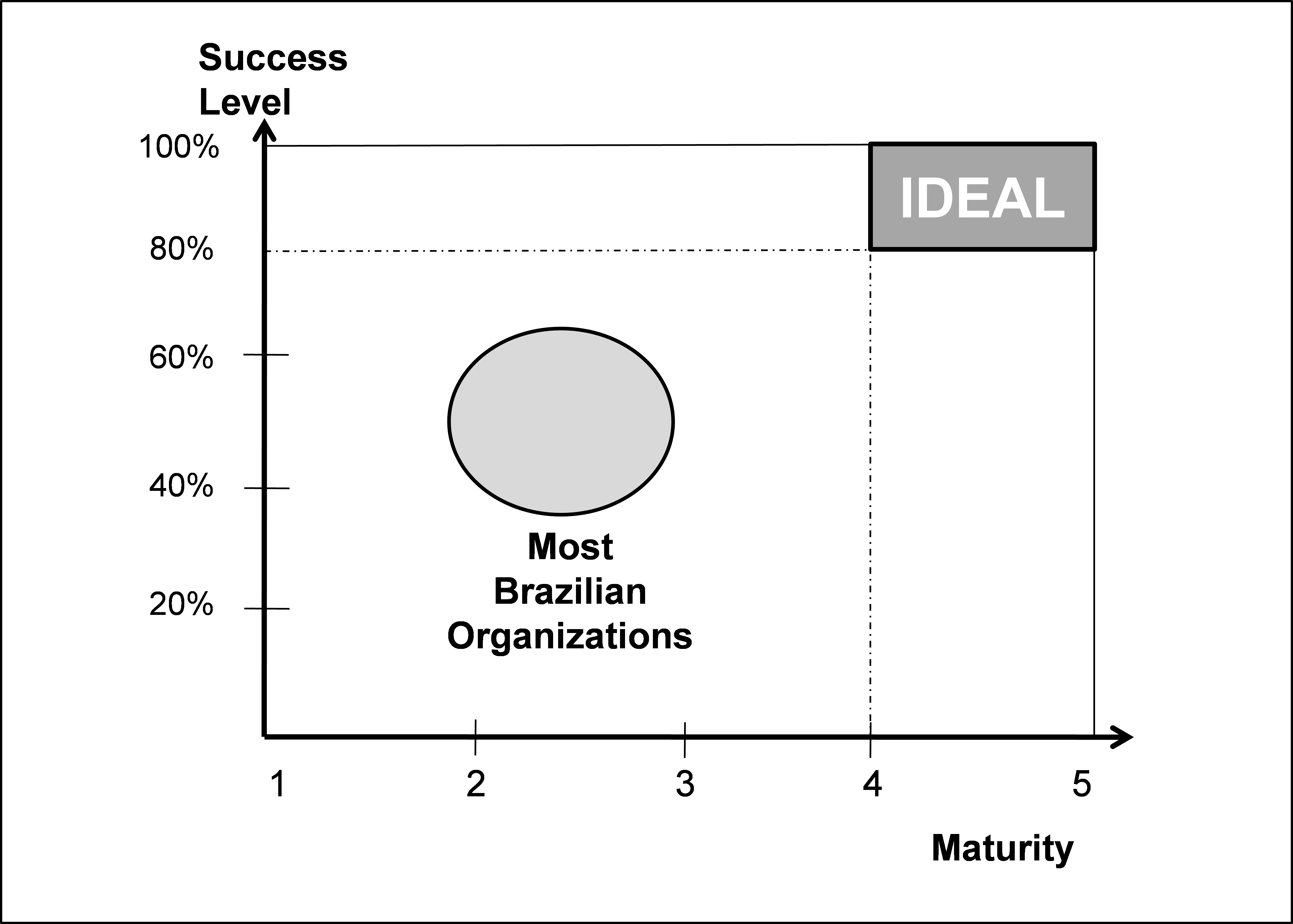

The situation in Brazil shows that most of Brazilian organizations are located in the circle shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Average Project Success Level versus PM Maturity Level in Brazil-2012.

Analyzing figures 5 and 6 it is very clear that to be at levels 4 or 5 puts the organizations in a very competitive situation. But here we have three questions.

The first question is: how to achieve this position? The answer seems, initially, to be very easy: positive evolution and continued improvement in project management in all the dimensions measured by the Prado PM Maturity Model will allow an organization to achieve a high level of maturity and project success. Doing that, the organization will join a very select group of organizations. This path is open to all organizations and will lead to increased competitiveness that will help to ensure prosperity and survival in today´s highly competitive global marketplace at both the company and country levels.

The second question is how long is this path? According to the internationally recognized PM authority Dr. Harold Kerzner [4], this evolution typically requires about 7 years of improvement effort for large organizations. Our experience in Brazil points in the same direction.

The third question is when should an organization enter this path? Certainly the answer to this question depends of a series of factors, from the level of dependency on projects to the overall success of the organization. But, as a broad statement, we may say that as soon an organization starts this evolution, it has a greater possibility of arriving at excellence levels earlier than the other organizations.

8 – Some Other Studies and Research Reports

The question about the value that project management brings to organizations and its relationship with maturity in project management, has been reported for many years in several studies around the world, especially in the studies of Ibbs and Kwak (1997), Kwak and Ibbs (2000), Ibbs (2000), Ibbs and Kwak (2000), Ibbs and Reginato (2002), Cooke-Davies et al (2003), Pennypacker and Grant (2003).

The study organized by Thomas and Mullaly (2008) called “Researching the Value of Project Management“, performed a thorough analysis of this issue of the value of project management through multiple case studies and found, among other conclusions, that:

- The maturity is a value in itself, especially when there is significant emphasis on processes´ outcomes;

- The value seemed to increase as the implementation of project management maturity is increased;

- Most organizations realize there are more intangible values gained than tangible values, and there´s a difficulty and even a disinterest in measuring tangible values of project management;

- The achievement of intangible value is correlated directly with the PM maturity: higher levels of intangible value are reported in organizations with a higher level of PM maturity;

Therefore, we see that the Brazilian research corroborates with the Thomas and Mullaly (2008) study, because the result of the analysis between maturity level and perceived value of project management converges with the their conclusions.

The Brazilian research also corroborated with the Thomas and Mullaly (2008) study, with its amazing simplicity, in respect to the relationship between success and maturity, as the Brazilian research achieved an excellent correlation between these variables, while the study of Thomas and Mullaly unfolded on the subject of success of projects through a complex but important principal component analysis (PCA).

Therefore, due to the complexity of the question of the value of project management, we believe that Brazilian research using the Prado-PMMM can become a “proxy”[3] measure of the success of the projects and even the value of project management in the organization, due to its easily application and interesting correlation with the success and value aggregation.

9 – Final Considerations

In future articles in this series we will deepen the presentation of results of the Brazilian Experience for several different categories of projects.

It is Important to point out that the model has been used successfully in Italy, Portugal, Spain, USA and Mexico. In Italy, a survey was conducted along the lines of the Brazilian research.

REFERENCES:

Cooke-Davies, T. J., & Arzymanow, A. (2003). The maturity of project management in different industries: An investigation into variations between project management models. International Journal of Project Management, 21(6), 471.

Kwak, Y. H., & Ibbs, C. W. (2000). Calculating project management´s return on investment. Project Management Journal, 31(2), 38-47.

Ibbs, C. W., & Kwak, Y. H. (1997). The benefits of project management: Financial and organizational rewards to corporations. Sylva, NC: Project Management Institute.

Ibbs, C. W. (2000). Measuring project management´s value: New directions for quantifying PM/ROI. PMI Research Conference. Paris, France.

Ibbs, C. W., & Kwak, Y. H. (2000). Assessing project management maturity. Project Management Journal, 31(1), 32-43.

Ibbs, C. W., & Reginato, J. M. (2002). Quantifying the value of project management. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Pennypacker, J., & Grant, K. (2003). Project management maturity: An industry benchmark. Project Management Journal, 34(1), 4-11.

Thomas, J., & Mullaly,M. E. (2008). Researching the value of project management. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

This article has been published by PM World Journal at http://pmworldjournal.net/

About the Authors

Russell D. Archibald

San Miguel de Allende, Mexico

![]()

![]()

Russell D. Archibald: PhD (Hon) ESC-Lille (Fr), MSc (U of Texas) & BS (U of Missouri) Mechanical Engineering, PMP, Fellow PMI and Honorary Fellow APM/IPMA (member of the Board of IPMA/INTERNET 1974-83), held engineering and executive positions in aerospace, petroleum, telecommunications, and automotive industries in the USA, France, Mexico and Venezuela (1948-1982). Russ also had 9 years of active duty as a pilot officer with the U.S. Army Air Corps (1943-46) and as a Senior Pilot and Project Engineer with the U. S. Air Force (1951-58.) Since 1982 he has consulted to companies, agencies and development banks in 16 countries on 4 continents, and has taught project management principles and practices to thousands of managers and specialists around the world. He is co-author (with Shane Archibald) of Leading and Managing Innovation: What Every Executive Team Must Know About Project, Program, and Portfolio Management (2013); author of Managing High-Technology Programs and Projects (3rd Edition 2003), also published in Russian, Italian, and Chinese; other books (in English, Italian, Japanese, and Hungarian); and many papers on project management. Web-site: http://russarchibald.com E-mail: russell_archibald@yahoo.com

Darci Prado, PhD

Minas Gerais, Brazil

![]()

Darci Prado is a consultant and partner of INDG in Brazil. He is an engineer, with graduate studies in Economical Engineering at UCMG and PhD in Project Management from UNICAMP, Brazil. He has worked for IBM for 25 years and with UFMG Engineering School for 32 years. He holds the IPMA Level B Certification. He was one of the founders of Minas Gerais State and Parana State PMI chapters, and he was member of Board Directors of Minas Gerais State PMI chapter during 1998-2002 and member of the Consulting Board during 2003-2009. He was also the president of IPMA Minas Gerais State chapter during 2006-2008. He is conducting a Project Management maturity research in Brazil, Italy, Spain and Portugal together with Russell Archibald. He is author of nine books on project management and is also author of a methodology, a software application, and a maturity model for project management. Darci can be contacted at darciprado@uol.com.br

Warlei Agnelo de Oliveira

Belo Horizonte, Brazil

![]()

Warlei Agnelo de Oliveira, MsC, is a Secretary of Transportation and Public Works Advisor and is currently the Project Manager of the “Belo Horizonte Metro” re-structuring project. With a bachelor degree in Civil Engineering, Warlei also holds a MBA degree in Project Management from FGV and a M.Sc. degree in Business Administration. He is Orange Belt / ILL certified and is currently Professor of Civil Engineering and Environmental Technologist at Centro Universitário UNA.

[1] The Project Management Maturity series of articles by Russell Archibald & Prof Darci Prado is based on their extensive research on this topic in Brazil, the United States and other countries. Russ is one of the pioneers in the project management field and the originator of the Archibald Project Categorization Model. Darci is the developer of the Prado Project Management Maturity Model which has been successfully implemented by many organizations in Brazil. This month they have added Warlei Oliveira in Brazil to their writing team. More about this model and related research can be found at http://www.maturityresearch.com/.

[2] These 28 questions can be found on the site www.maturityresearch.com by registering and then clicking on the

“Start Evaluation” button. You can read all questions in both questionnaires there without actually giving

answers to the questions. The corporate identity of organizations is not revealed in the study results.

[3] The proxy is a statistical definition for a variable which in itself would not have much relevance, but, if one variable has a strong correlation with another, could be of great interest. Such variables are often used in studies of the economy where, for example, we can measure the income receipts of a city by power electricity consumption. In that case the power electricity consumption would be the “proxy”.